COVID-19 anxiety is real and mutual fear-mongering, misinforming and denialism have become common social media responses to the pandemic.

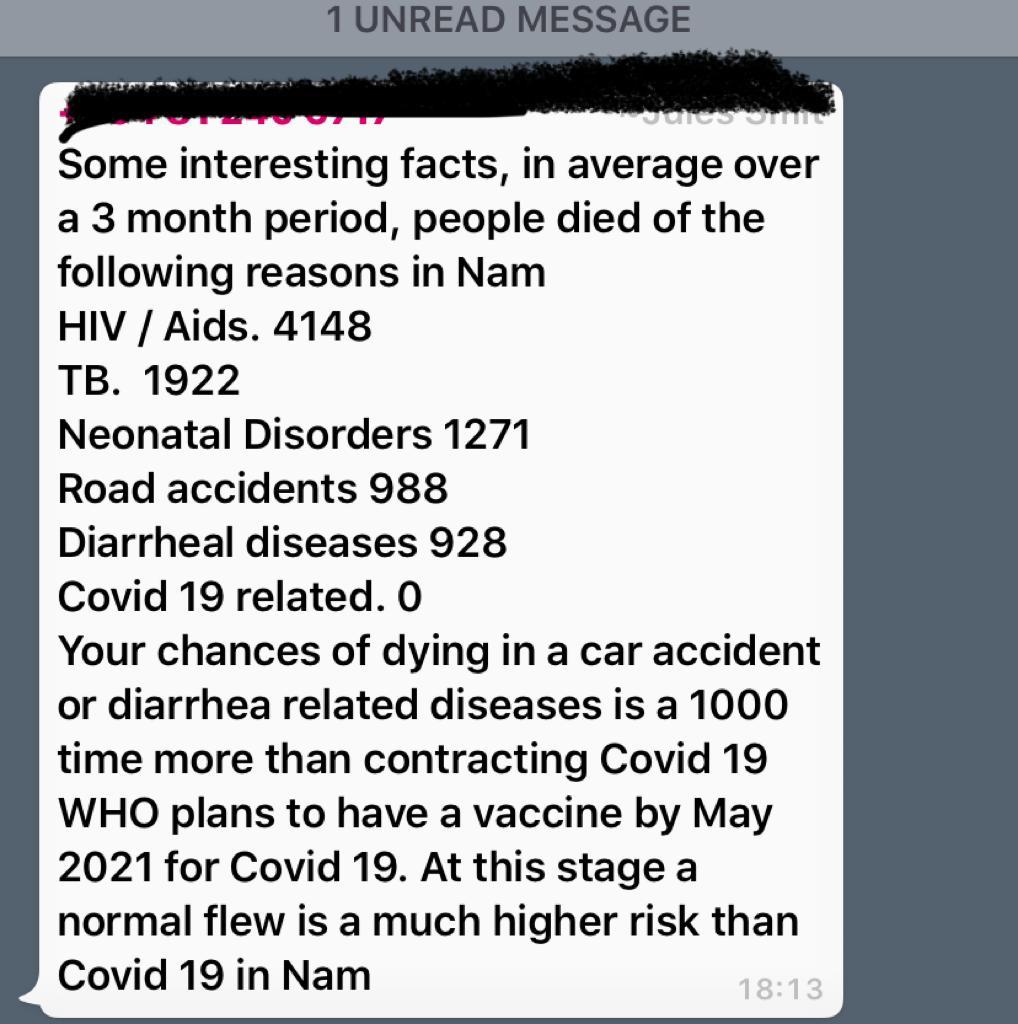

We’ve all now encountered the emotional outbursts and outpourings on WhatsApp; the sworn-by cures and remedies on Facebook; the truth-exposing voice notes; the all-revealing memes.

Fear and anxiety are normal responses in the face of ballooning uncertainty, such as the COVID-19 pandemic which has been ravaging humanity physically, psychologically and emotionally for seven months now, with no end in sight yet to the multi-layered ordeal.

With Namibia’s infections ticking up in late June 2020, just as the already economically stressed country emerged from a nationwide lockdown and as restrictions on various socio-economic activities remained in place – which has further exacerbated job and livelihood losses and business closures – the fears and desperation of many have found expression on social media platforms.

Exemplifying this fear and desperation, in June 2020, a petition was shared among Namibian WhatsApp groups and on other social media platforms calling on the government to open the borders to tourists in order to stimulate a resurgence in the sector so that people could earn a living. The petition stated:

“Here in Namibia thousands of jobs are at risk if the government does not step in urgently to support the travel & tourism industry through clear information and by opening borders as soon as mid-July 2020, without any quarantine measures in place for international visitors.

“Many of us no longer have the money necessary to meet the daily expenses of our families: who will pay for our rent, children school fees, food and transport? Most businesses have been trying to keep us employed because they all know that when we lose our job the chances to find a new one now is almost impossible, but when there is no more money, they will also no longer be able to help us.

“Keeping the borders closed will lead to very high and long-term unemployment in Namibia. The death and suffering due to malnutrition & hunger, lack of medical treatment for many other illnesses such as TB, aids, etc, increased crime due to desperation of those without any income will far exceed any COVID-related deaths in the very near future.”

In many instances, this sort of fear and desperation have taken the forms of denying or downplaying the impacts and severity of COVID-19 to sharing and supporting unfounded conspiracy theories and outright labeling the pandemic a hoax and the measures to contain the spread of the virus a malicious attempt to destroy lives. The effect has been that the COVID-19 information ecosystem has become a disinformation cesspit, with many people openly expressing and displaying a sense of distrust in any official sources of information.

Causing anxiety

A large part of the problem is people’s exposure to the flood of COVID-19 related information – including false and misleading information – since the pandemic started in China in December 2019.

And social media haven’t helped, as the platforms have become the melting pots in the disinfodemic which has accompanied the pandemic from the beginning. For instance, researchers have recently found that Facebook groups were ‘super-spreaders’ of disinformation because of how they work algorithmically. With increasing numbers of people primarily turning to their social media feeds for COVID-19 related information it is thus no wonder that the information ecosystem has become polluted with falsehoods and hoaxes, driving up anxiety and mental distress levels.

Continued or over exposure to media coverage hasn’t helped either. A Dutch study, titled ‘Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19)‘, the results of which were released in May 2020, observed that:

“Particularly, the observed relationship between media exposure and fear of the coronavirus suggests that more exposure to media can lead to more fear.”

The researchers suggested that:

“If this is indeed the causal connection between these constructs, then there are opportunities for policy makers and journalists to affect excessive fear. One way to do this is to ensure that communication is clear and unambiguous, because uncertainty tends to increase fear. Information should also be provided without sensationalism or disturbing images. In addition, there are also opportunities for individuals themselves to tackle their fear. People can be advised to somewhat restrict their exposure to media coverage of the corona crisis (e.g., to check media sources only a limited number of times per day and not continuously throughout the day) and avoid sensational media, which may enhance stress and decrease well-being.”

And they cautioned:

“Our results may also be taken as indicative that stronger messages in the media may induce more fear and therefore more compliance with the social distancing and lock down policies imposed. However, we caution against using media messages to induce more fear in the general public. Particularly, there is evidence that suggest that such ‘fear appeals’ do not work very well to promote behavior change, particularly when people have little coping strategies. Under such circumstances, which may apply to the current coronavirus crisis, it may not be very helpful to maximize fear, as this may only increase distress.”

In light of this, that people want things to go back to normal is an understandable impulse under the circumstances, but the fact is that downplaying or negating the dangers of COVID-19 – by spreading and proclaiming falsehoods and hoaxes – will not make things better, but could cause further disruption and prolong hardships.