Image: Namibia Fact Check / Canva

Conspiracy theories have infected social media and pollute the COVID-19 information space. Why is this happening?

By now most Namibians with a social media presence will have encountered one or other elaborate conspiracy theory about the origins and spread of COVID-19, and many will probably have run up against one in particular – ‘Plandemic: The Hidden Agenda Behind Covid-19’ – which has been all over social media since early May 2020.

How the ‘Plandemic’ has gone viral and global has been an eye-opener for many in the media and fact checking spheres and has exemplified the dangers of the disinfodemic that has swept the world like never before since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ‘Plandemic’ video has featured on Facebook, trended on Twitter, exploded on Youtube and been widely shared in Namibian WhatsApp groups. And as it traveled, all these platforms have struggled to shut it down.

What follows is a synthesising of research and insights of how this conspiracy theory, and similar ones since then, have managed to find captive audiences the world over.

What happened?

To get an idea of what happened, this is how a 1 June 2020 Buzzfeed News article described what unfolded:

Featuring scientist Judy Mikovits, whose history includes a retracted paper, being fired by her research institution, and jail time, the video became a centerpiece of coronavirus disinformation after it was released on May 4. When it was first published, it outperformed legitimate content and spread across the web faster than fact-checkers could debunk it.

But even though the video centered on the United States, seeking to discredit National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases head Dr. Anthony Fauci, it found an audience abroad, too. The video was shared in Facebook groups in a dozen languages including Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, German, Polish, Armenian, and Tagalog, as well as English-language groups across Africa. It was also translated and either subtitled or dubbed into at least 13 different languages so that local audiences could understand it.

– Buzzfeed News

The author of the article, Jane Lytvynenko, states of the phenomenon:

The result is evidence that while the United States constantly worries about foreign disinformation operations, the country exports false information as well.

– Jane Lytvynenko / Buzzfeed News

Since the 4 May 2020 release of the video, numerous fact checkers and scientists around the world have debunked the claims and statements made in the video, but it just kept going despite this and the continuous take-downs by social media platforms.

Who is behind it?

It’s clear that many of the conspiracy theories – anti-vaccination, anti-WHO, anti-Bill Gates, anti-5G, etc. – do not originate in Namibia, or even Africa, but have mostly come from the US and Europe. Some of the originators of such conspiracy theories have been spreading their false information for years within the limited circles of the like-minded, but have suddenly gained international audiences and notoriety as their conspiracies have gone global on the back of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the case of ‘Plandemic’, the producers and central figure – Judy Mikovits – are known conspiracy theorists with close ties to anti-vaccination groups and movements in the US, and even to the bizarre US conspiracy theory cult that is QAnon.

Adrienne LaFrance, the executive editor of the US’s The Atlantic, in a recent interview described QAnon as follows:

“QAnon is a conspiracy theory. The basic premise is that Q is a military insider who has proof that a secret group of world leaders are working with the deep state to torture children and that Donald Trump is aware of this and working to fight them. Q posts clues on the internet known as “Q drops” that advance these ideas. It’s a real-time, participatory conspiracy theory.”

[Plandemic] is extremely QAnon-esque. It borrows a lot of the same language and narrative structure, if you can call it that. The same people who promote QAnon are now promoting Plandemic. The video fits very squarely within the QAnon worldview.

– Adrienne LaFrance

For more insight on this conspiracy theory and the thinking behind it, here’s the June 2020 cover story of The Atlantic.

How is it happening?

According to First Draft, in a 21 May 2020 article, ‘Plandemic’ has achieved global virality because of three factors:

- Content lives beyond platform removals: “You had content pulled down from platforms after a few hours, and the platform companies are like, ‘See how fast we did this, this is amazing!’” [Joan Donovan, research director of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center] explained. “But you see, instantly, hundreds of copies of it going up all over the web.”

- You won’t always be able to attribute suspicious activity: “When it comes to domestic actors, people are perfectly capable of creating and sharing and making misinformation go viral themselves without having a big evil troll factory.” Said Donie O’Sullivan, a reporter at CNN.

- Communities are increasingly coming together: Supporters of a variety of conspiracy theories have united in their scepticism of mainstream narratives during the coronavirus crisis. The “Plandemic” video tapped into familiar conspiracy theories that claim a shadowy group of elites is hoping to gain power, this time through the virus. – First Draft.

Why is it happening?

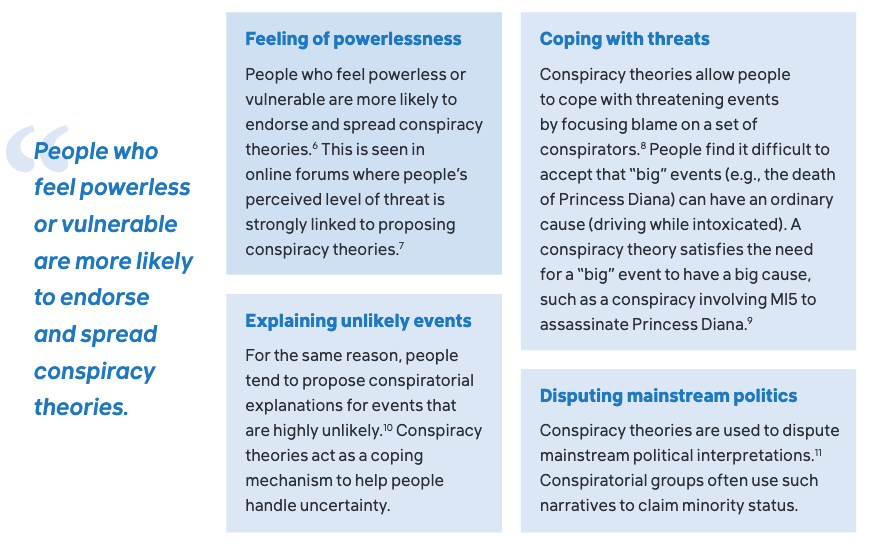

People are scared. People are looking for answers. People want things to make sense. Some people also want someone to blame for how COVID-19 has affected their lives. And some people are exploiting the pandemic for financial and influence gain. That’s why ‘Plandemic’ has traveled further than other conspiracies.

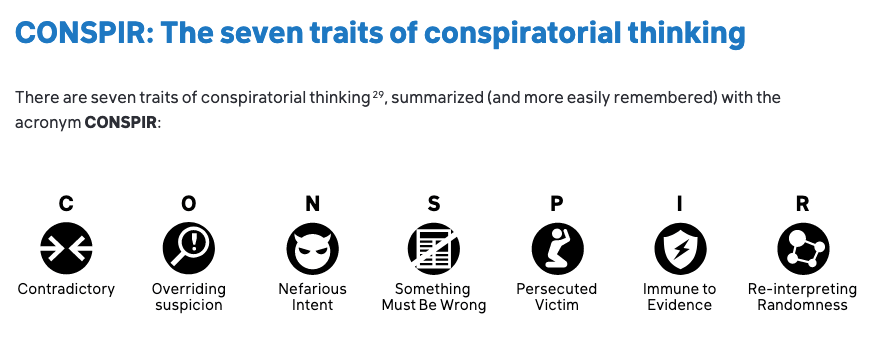

According to The Conspiracy Theory Handbook this is what it looks like:

And here’s something else to note in all this:

What should also be emphasised, is that the producers of disinformation are often doing what they’re doing to profit from their conspiracies and hoaxes, according to a recent article by Cristina Tardáguila, who is the associate director of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN).