Image: Namibia Fact Check / Government Gazette

It’s an offence to spread false information about COVID-19 during the state of emergency period. But what does this actually mean?

As the weeks-long Namibian lockdown period, imposed under the state of emergency instituted in March 2020, drew to a close on 16 April 2020, the lockdown was extended until 4 May 2020, and new regulations were issued. Among the regulations were measures criminalising the spreading of false information about the COVID-19 pandemic and the responses to it.

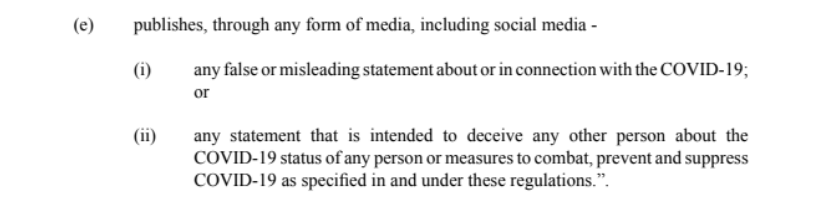

The new state of emergency regulations, dated 17 April 2020, state under regulation 15 that “(1) A person commits an offence if that person –”

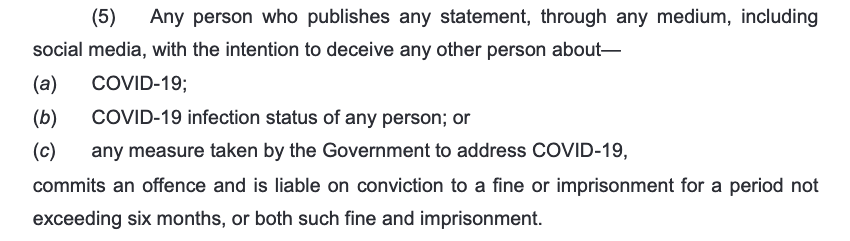

These provisions seem fairly similar to and mostly a replication of the anti-disinformation measures gazetted by the South African government, in relation to its COVID-19 disaster management plan, on 18 March 2020. The South African regulations state under regulation 11 the following:

However, while these regulatory measures share similarities, there are also marked differences:

- The Namibian regulation criminalises, firstly, the publishing of “any false or misleading statement”, and, second, “any statement that is intended to deceive” in the context of COVID-19;

- The South African regulation only criminalises the publishing of statements “with the intention to deceive” and not “any false or misleading statement”.

This is an important distinction in articulation, for the blanket criminalising of “any false or misleading statement” in the Namibian regulation appears to mean that anyone who, even unwittingly, “publishes” false information could face criminal sanction. This is significant because it suggests that a person who “publishes” information they believe to be true, but turns out to be false, on their social media feed could be criminally fined or prosecuted. Similarly, any journalist, with no intention to deceive, who “publishes” information that they thought was true, but is not, at the time of publication could be criminally charged for publishing such information.

Now, in terms of social media, which is where the vast majority of COVID-19 related false information is published, the following questions remain unclear with regard to the Namibian regulation:

- Does ‘reposting’, ‘forwarding’ or ‘sharing’ false information constitute publication or does criminal liability only fall on the actions of the original poster or author of “false or misleading” information?;

- How does this regulation align with the constitutional protection of freedom of expression and media freedom?

The first question around ‘reposting’, ‘forwarding’ or ‘sharing’ disinformation speaks to the fact that much, if not most, of the false information, hoaxes and conspiracy theories circulating around COVID-19 on Namibian social media emanates from somewhere else. So the issue of who could be held liable for such content becomes highly pertinent and remains unexplained, a week after the regulation was gazetted.

The second question is important to consider because not even during a state of emergency can freedom of expression and media freedom (as contained in Article 21 (1) (a)) be revoked or suspended, according to Article 24 (3) of the Namibian Constitution.

At the time of writing this article no-one had yet been arrested or charged with contravening regulation 15 (1)(e), so it remains hard to assess how this regulation will be interpreted and applied when enforced.

Namibia Fact Check will monitor the situation with regard to regulation 15 (1)(e) and will update if and when more clarity is available.